Much faster than the dollar or the yuan, the currency of knowledge is being devalued. When it hits zero, those betting on questions will prosper.

The Answer to Everything

In Douglas Adams’s book The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, a group of hyper-intelligent beings builds a supercomputer named Deep Thought to calculate “the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything”. After seven and a half million years of computing, Deep Thought finally replies:

“The Answer to the Great Question of Life, the Universe and Everything… is… forty-two.”

This did not go well with the programmers, who expressed their disappointment to the computer.

“It would have been simpler had I just computed the Ultimate Question itself. But I can’t.”, replied Deep Thought.

“Can’t?” the programmers cried in astonishment.

“No,” said Deep Thought. “I speak with all the authority that 7.5 million years of computation can confer. But I do not know the Question. To understand the Answer, you must understand the Question.”

“So what do we do?” asked the programmers.

Deep Thought replied, “I shall design for you a computer. A computer so complex that organic life itself will form part of its operational matrix. And you yourselves shall take on new forms and go down into it, to operate its system as part of its programming team. And this computer will be called…”, he paused, “the Earth.”

So what is more important? The answer or the question?

Don’t panic. Read on.

The Knowledge Era: Greeks, Renaissance, Modernism, Turing

When Alan Turing proposed his famous Imitation Game (we now call it The Turing Test) he specifically stated “…I believe it to be too meaningless to deserve discussion” whether “machines can think”. But by then, after over 2500 years of indoctrination, being able to answer, to know like a human, has become the hallmark of intelligence.

Plato, Aristotle, Leonardo, Galileo, Copernicus, Newton, Voltaire, Lock, Kant. “Sapere aude”, “Dare to know”, became not just a noble ideal but a moral imperative. We built our society around this ideal. We taught and measured our youth by how much they know. We invest to become experts, value and pay for their opinions, and argue about which knowledge is correct and which is not.

According to this ideal we built better tools and machines until we reached the ultimate goal. An all-knowing oracle. It will soon pass the Turing Test (if it hasn’t already), but does that mean we can lay back and let it take us to Utopia? If “knowledge is power” do we now have the power to do anything? Far from it.

Now that knowledge has become abundant, we need to acknowledge it is completely useless by itself. We need to change our mental direction (and perception of value) from “knowing” to “asking”. Two things that have been at opposing ends of where one needs to strive.

The Subtle Art of Not Knowing

Being able to ask questions is much harder than one might expect. It does come naturally to us as kids (to the extent of driving parents mad) but we are taught to value knowing, not questions, and lose or inhibit this ability.

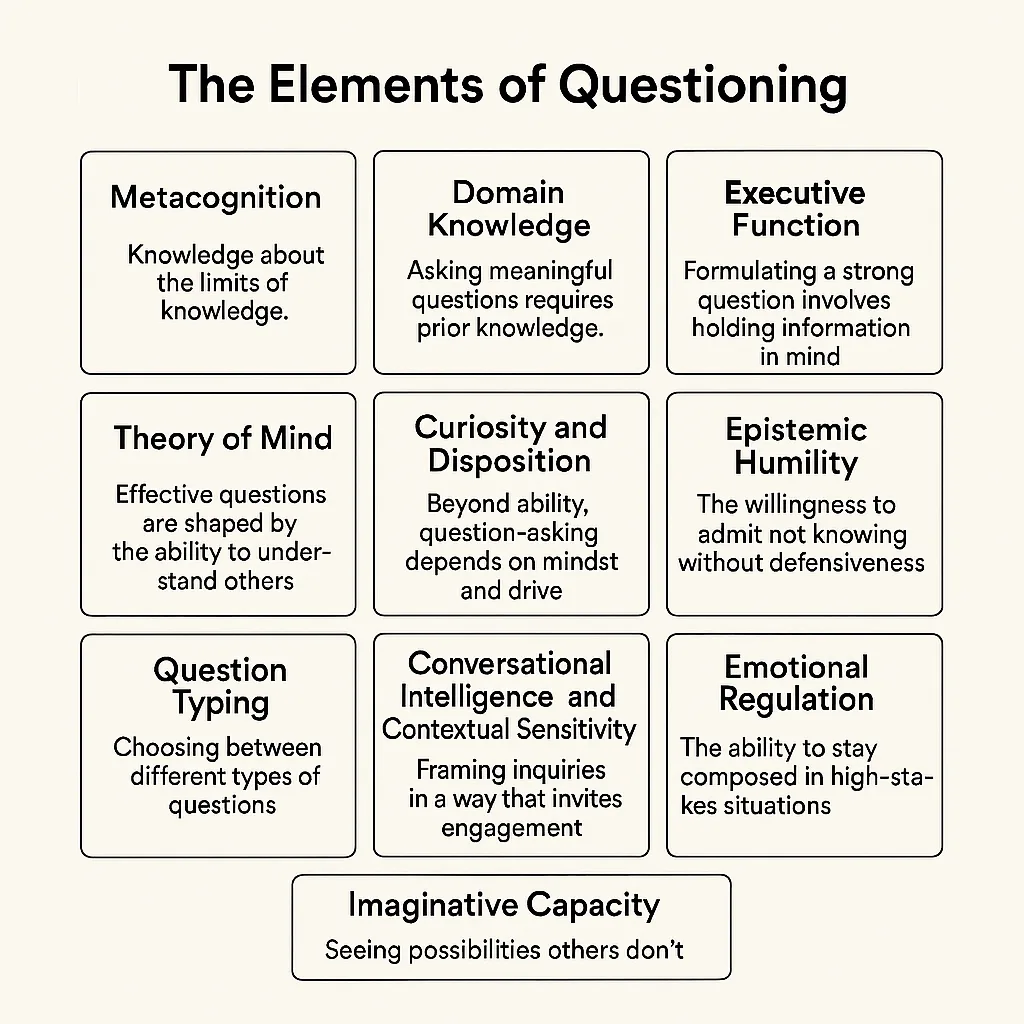

Here’s the list of things science and philosophers consider the pillars of being question-oriented. Test to see how good you are at any of them. No pressure. It is only your prosperity and that of humanity that is at stake.

- Metacognition – Knowledge about the limits of knowledge. Being able to scan your inner self, identify gaps and form questions that target those gaps.

- Domain Knowledge – Asking meaningful questions requires prior knowledge. Familiarity with a domain helps recognize what’s missing, frame your questions with precision and interpret responses.

- Executive Function – Formulating a strong question involves holding information in mind, focusing attention and resisting easy answers.

- Theory of Mind – Effective questions are shaped by the ability to understand what others know, believe, or need.

- Curiosity and Disposition – Beyond ability, question-asking depends on mindset and drive. It takes openness to uncertainty and a desire to find out.

- Epistemic Humility – The willingness to admit not knowing without defensiveness. This is a big deal. It is also a cultural thing. Keep an eye for societies that tolerate and even encourage this trait.

- Question Typing – Skilled questioners know that not all questions are the same. They choose intentionally between clarifying, exploratory, hypothetical, or evaluative questions depending on context and purpose.

- Conversational Intelligence and Contextual Sensitivity – These include reading the room, adapting tone, and framing the inquiry in a way that invites engagement rather than defensiveness or confusion. Since we are talking about the age of AI, this might sound absurd. But remember we will soon work in hybrid teams and in that context, knowing who/what and when to ask, will be crucial.

- Emotional Regulation – In situations that are high-stakes, uncertain, or emotionally charged, the ability to stay composed, counts. It allows for listening, reflection, and persistence.

- Imaginative Capacity – Some of the most powerful questions come not from gaps in information, but from creative insight, seeing possibilities others don’t.

Difficult terms, more difficult to implement. Feel the tension of saying “I do not know” to any of the following “knowledge” provoking statements:

“Are the Trump Tariffs a good or bad idea?”

“Rushing your kids to bed on a school night is the right thing to do?”

“Should you take a loan to invest in the stock exchange?”

“Are fluoride toothpastes good for you?”

“Should you quit your job and start a business?”

“Are GMOs a thing we should ban or encourage?”

“Should the marketing department you lead change its focus?”

The Knowledge Paradox

What’s more, we’ve hit a paradox. To be effective at questioning, one needs to know. But to know is not to question. Down goes the rabbit hole.

The solution lies, I’m treading softly on speculative ground here, at implicit vs explicit knowledge. We discussed it briefly in a previous post. Fact recollection, calculations and even strong theory replication will not be required. Intuitive understanding, inter and cross domain inference and the ability to move from implicit to explicit and fuzzy-explicit (the machine will fill the blanks) will be the winner.

How to train for that kind of thinking? I predict by encouraging what is already natural for our brain. Not fact recollection and preciseness but broad associations and non-linear and stacked pattern recognition. But honestly I do not know. It is an open question.

An Economic Incentive. With an Asterisk

Remember the “It is only your prosperity and that of humanity that is at stake” statement from above? Was no joke. In every era, when there is an increase in the productivity gained from capital (i.e. technological progress), the labor (people’s work) associated with that increase, also grows in value (when the labor is contributing. Not replaced).

And vice versa. If labor does not contribute to the yield increase, or is replaced, the result is growing social inequality, which usually ends badly. (Read this book for details, it’s amazing). Two groups will “run off”, the one with capital (through the increased returns) and the one contributing to the capital yield, surfing their growing salaries away from the rest (for a rather recent study on the subject see here, though what is claimed there about college education is becoming obsolete very fast).

The most valued labor will shift, from experts with answers to doubters with better questions.

These are the people we need to train through the education system and these are the people we need to become.

There is just one little dark asterisk to add here.

AI Agents. It is easy to imagine how they do the “replacing” trick in the above capital-techno-yield scheme. There is no need for an inquisitive human if the machine can do both the questioning and the answering. True but the machine needs to have motivation in order to question. Even setting goals and letting the Agent reach them autonomously requires motivation. And we are still very far from a motivated Siri. No motivation, no unemployment. If we become humble enough to stop knowing.

The Cognitive Shift

To finish with a bit of optimism, here’s my take on how we are going to trust knowledge in the near future. We are not. No facts given on any medium by any person will have any weight. The good news is there’s no fake-news. Not because we can’t trust anything due to deepfakes, but because of the first law of economics. For something to have value, it needs to be scarce. When knowledge requires no effort to retrieve, it loses its value.

Value will be in the motivations that produce the best results. Which motivations are these, and what results should they aim for? Easy. 42.